James M. Dorsey: Why Morocco could beat Saudi world cup bid

The World Cup is likely to produce headwinds for the Saudis. Not only because it involves not one, but two of the world’s most serious violators of human rights, but also because it will encounter stiff competition. Morocco’s bid however might just be the message that FIFA are looking for after Qatar

Activists, athletes, and the soccer associations of Australia and New Zealand will celebrate their thwarting of world football body FIFA’s plans to accept Saudi Arabia’s tourism authority as a sponsor of this year’s Women’s World Cup.

FIFA president Gianni Infantino admitted as much at a news conference convened this week shortly after he was re-elected unopposed for a third term, even if he belittled it as “a storm in a teacup.”

Nevertheless, the thwarting sent a rare message that money can buy a lot but not everything.

It constituted the first setback in a string of successful Saudi bids to sponsor or host everything under the sporting sun.

Despite its abominable and worsening human rights record, Saudi Arabia has secured hosting rights for the Asian Football Confederation’s 2027 AFC Cup, the Olympic Council of Asia’s 2029 Asian Winter Games, and the 2034 Asian Games.

A regional human rights group, ALQST for Human Rights, has asserted that at least 47 members of the Howeitat tribe in Saudi Arabia have been arrested for resisting eviction to make way for Neom, a US500 billion futuristic science fiction-like region under development on the Red Sea.

Trojena, a mountainous part of Neom, is where the Winter Games are scheduled to be held.

Saudi Arabia is also bidding to host the 2026 AFC Women’s Asian Cup, and, together with Greece and Egypt, the 2030 World Cup.

The World Cup, like this year’s women’s tournament, is likely to produce headwinds. Not only because it involves not one, but two of the world’s most serious violators of human rights, but also because it will encounter stiff competition.

A joint bid by Morocco, Spain, and Portugal could prove to be a serious challenge on multiple fronts to the Saudi-led effort.

It represents a trans-continental bid that, unlike the Saudi-led proposition, is not designed to circumvent FIFA’s practice of spreading out the tournament across continents.

On its own, Saudi Arabia, as a Middle Eastern state, would not stand a chance so short after last year’s World Cup in Qatar.

The circumvention element is borne out by the kingdom’s willingness to fund all of Greece and Egypt’s World Cup-related expenses in exchange for the right to host three-quarters of the tournament’s matches in Saudi Arabia.

Moreover, the Moroccan-Spanish-Portuguese bid is likely to spark less controversy than its Saudi-led competitor.

While Qatar demonstrated that human and migrant rights criticism need not put a serious dent in the reputational benefits of hosting a sporting mega-event, it also showed that once a focal point of attention, always a focal point of attention.

Three months after the Qatar World Cup final, one million people signed a petition demanding the Gulf state compensate workers and/or their families who had been injured or died or suffered human rights abuse while working on tournament-related projects.

READ: Morocco’s team out of World Cup but players “heroes”

For Morocco, winning the bid would have special significance. Coming on the back of its darling status during the Qatar World Cup, a win would amount to payback for Saudi opposition to Morocco’s failed effort to secure the 2026 tournament hosting rights.

Saudi Arabia supported the winning US-Canadian-Mexican bid as a way of punishing Morocco for its refusal to back the 3.5-year-long UAE-Saudi-led diplomatic and economic boycott of Qatar. The boycott was lifted in early 2021.

Perhaps the strongest headwinds the kingdom’s sports effort has encountered emanate from its controversial creation of LIV Golf, a US$405 million, 14-tournament league, to compete with PGA Tour, the longstanding organizer of the sport’s flagship events.

LIV Golf is “an exercise in public relations. A foreign government’s dollars are being used to enhance that government’s brand and positioning here in the United States,” US Congressman Chip Roy, a Texas Republican, said.

Even worse, circumvention was at the core of a ruling last month by a US federal judge ordering Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF), to answer questions and produce evidence as part of the discovery process in a legal battle between LIV and PGA. The PIF funds LIV Golf.

The discovery could cast a spotlight on the secretive fund’s decision-making. The fund’s powerful governor, Yasir Al-Rumayyan, is a Cabinet-level official.

Judge Susan van Keulen’s ruling rejected an attempt by the PIF and Mr. Al-Rumayyan to evade turning over information connected to the courtroom battle because they allegedly enjoyed sovereign immunity as a state institution and official.

Earlier, US District Court Judge Beth Labson Freeman, an avid golfer, ruled that the PIF and Mr. Al-Rumayyan fell under a commercial exception to US laws on sovereign immunity.

Some analysts suggest that Mr. Roy’s comment and the judges’ rulings could lead to LIV Golf being deemed a foreign influence campaign.

This would mean that its employees in the United States would have to register as foreign agents under the Foreign Agent Registration Act, or FARA.

The rulings call into question assurances provided in 2021 to England’s Premier League to assuage concerns that the PIF’s acquisition of England’s Newcastle United Football Club would put it under the control of the Saudi state.

The League’s chief executive, Richard Masters, said at the time that the Premier League had been given “legally binding assurances that essentially the state will not be in charge of the club” and that if there was “evidence to the contrary, we can remove the consortium as owners of the club.”

The League has so far refrained from taking the PIF to task in the wake of the US rulings because the Newcastle agreement stipulated that the Saudi state would not exercise control over Newcastle, not that it would not have the ability to do so.

Lawyers for Newcastle said there would only be a case if the Saudi state used its power to intervene in the club’s affairs.

“There’s an unmistakable irony in the sovereign wealth fund declaration emerging in a dispute about another arm of Saudi Arabia’s growing sports empire, but the simple fact is that Saudi sportswashing is affecting numerous sports, and governing bodies need to respond to it far more effectively,” said Peter Frankental, an Amnesty International executive.

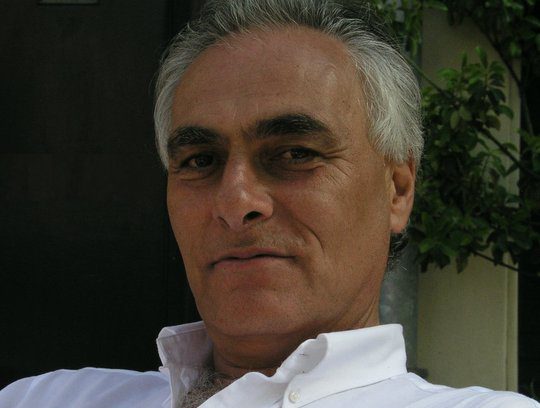

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and scholar, an Adjunct Senior Fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, and the author of the syndicated column and podcast, The Turbulent World with James M. Dorsey.