Ignacio Cembrero: The dark side of Morocco diplomacy with EU

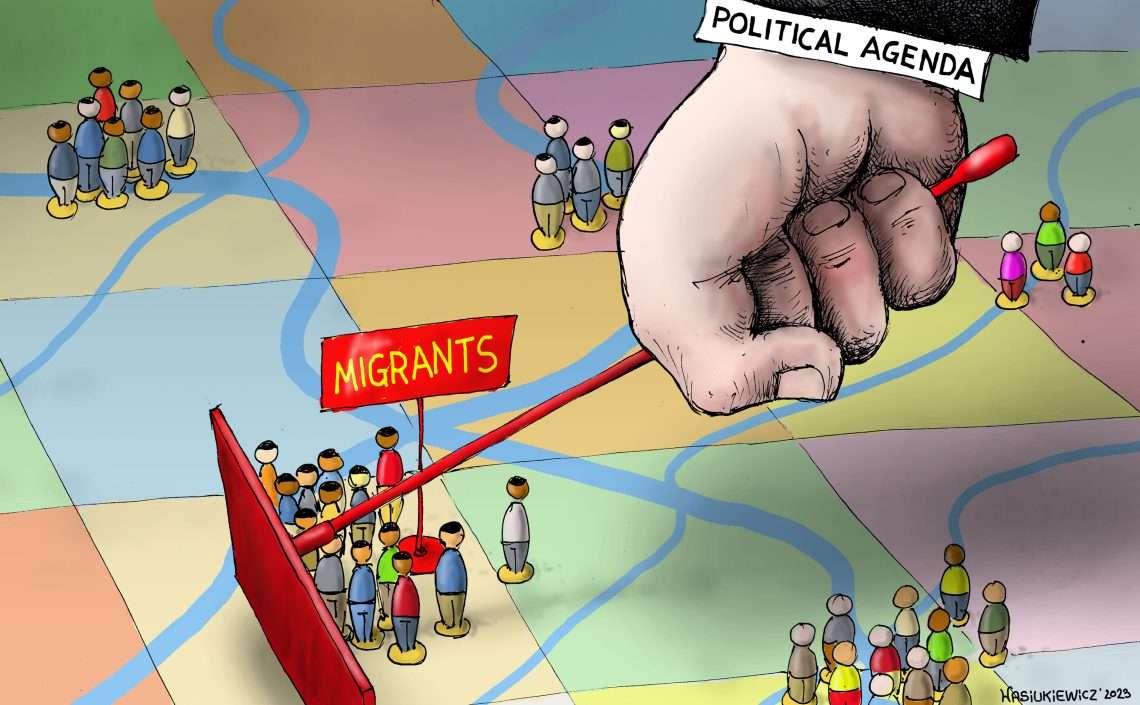

As previously covered here, Morocco’s endevours internationally with press management and diplomacy appear to fall short of any notable achievement – certainly not via conventional means. However Rabat uses blackmail – both with immigrants and the threat of blocking intelligence sharing on terrorism – to good effect. It’s even started silencing media in some EU countries on subjects which it prefers are kept under the carpet – meddling which EU governments would prefer was not widely known

The Belgian Justice has made the unprecedented decision to transfer the bulk of the investigation into Qatargate, the corruption plot in the European Parliament, to Rabat. Belgium thus gives the impression of giving in to Morocco.

The last to let its arm be twisted by the Kingdom of Morocco was Belgium. His Justice took in April, at the request of the prosecution, the unprecedented decision to let the two alleged instigators of Qatargate the largest corruption scandal in the history of the European Parliament, be investigated and, perhaps, tried in their own country. Both, a diplomat and a secret agent, with Moroccans who obeyed orders from their authorities. Does anyone believe that they will really be investigated?

Why, after 16 months of investigations, did the Belgian Justice decide to transfer to the Moroccan justice part of the summary of that Qatargate which should rather be called “MoroccoGate” because it was set up by Moroccans? The Belgian Prime Minister, Alexander De Croo, recalls the Brussels newspaper Le Soir traveled to Rabat around that time, together with three ministers, and obtained what he had longed for for years: to be able to repatriate Moroccan immigrants in an irregular situation to Morocco. A first group of 700 was going to be expelled shortly, as announced at the time.

If this hypothesis is true, Morocco would have demonstrated, once again, the not only economic, but also political, party that it is capable of drawing from its emigration to Europe. There are a few precedents before the recent Belgian episode worth noting.

Three years ago, Morocco and the Netherlands signed an agreement on labor of which the Dutch Government refused to report in detail to Parliament until September 2022. It also speeds up the repatriation of immigrants, but it had a double counterpart. The Hague pledged not to interfere in Morocco’s internal affairs, meaning that none of its ministers could now, as Foreign Minister Stef Blok did in 2018, criticize, for example, the repression of the peaceful Riffian rebellion.

The second Dutch concession, to which, for now, Spain or Belgium have not yet submitted, stipulates that the Executive in The Hague will consult with the Moroccan government regarding the aid it grants to NGOs that develop projects in that country, according to the newspaper NRC Handelsblad . Does it mean to consult that Rabat has the right of veto?

Spain has suffered with ups and downs, for a quarter of a century, from what, in a display of bravery, the head of Defense, Margarita Robles, called “blackmail” and “threat” on May 20, 2021. She expressed herself in those astonishing terms. in the mouth of a socialist minister, just after more than 10,000 irregular immigrants, a fifth of them minors, had entered Ceuta in less than 48 hours.

The case of Spain

This massive entry, which the head of Moroccan diplomacy, Nasser Bourita, blatantly attributed to “police fatigue after the Ramadan festivities”, it could be argued damaged Morocco’s image, but served to finally defeat the Sánchez Government in the long crisis with the neighbor. Hence the beheading of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Arancha González Laya; the swerve over Western Sahara and so many other concessions.

READ: Morocco blocked 75,000 African immigrants from reaching EU

The other instrument of pressure that Rabat uses, in addition to immigration, is cooperation in the fight against terrorism, which many European police consider essential, because the majority of the attacks in the last decade have been perpetrated by people of Moroccan origin.

Morocco officially cut it off for a month once with Spain, in retaliation because the yacht on which King Mohamed VI was sailing had been mistakenly intercepted by the Civil Guard, on August 7, 2014, when it crossed the waters of Ceuta. On that occasion, Rabat combined the suspension with an immigration sanction: Nearly 1,100 “without papers” landed on the Peninsula on August 12, 2014. From their testimonies it is deduced that that day there was no obstacle to jumping into the sea.

With France, Morocco also interrupted its police and judicial cooperation for almost a year, from February 2014 to January 2015, when the country was being hit hardest by jihadist violence. In return, he achieved his greatest political feat in Europe, having the French National Assembly modify, in June of that year, the protocol of judicial cooperation with Morocco so that its top police chief, Mr Abdellatif Hammouchi, would not suffer an annoying experience in France again.

Mr Hammouchi was, on February 20, 2014, at the residence of the Moroccan ambassador in Paris, when the French judicial police knocked on the door with the intention of taking him before an investigating judge who was investigating three complaints of torture. He hastily fled the country. To compensate him, France awarded him the Legion of Honor a year later, a medal that he must wear along with those of police and Civil Guard merit imposed on him by successive Ministers of the Interior of Spain.

In addition to being a tool of pressure, immigration is a source of income for the Moroccan State – its remittances are equivalent to 8.5% of GDP, more than tourism

Most of the migration agreements signed with Morocco are a dead letter when they refer to adults and, even more so, to minors. Spain was a pioneer in April 1992 by signing the “readmission of illegally entered foreigners.” More than 30 years later, returns are being carried out in dribs and drabs. According to police sources, they range between 2% and 5% of irregular entries. Many of them are carried out by plane from the Canary Islands and are expensive. They require two police officers per expelled immigrant. The flights go to El Aaiún, the capital of Western Sahara, to underline that it belongs to Morocco.

The naivety of rulers and even the press is, at times, frightening when it comes to immigration. Everyone in France celebrated the arrival in Paris, in July 2018, of half a dozen Moroccan police officers and social workers who were going to interview, with a view to repatriating them, a group of minors who lived on the street and made the Goutte d’Or neighbourhood uncomfortable. The police returned, but no teenager returned to Morocco.

In addition to being a tool of pressure, immigration is a source of income for the Moroccan State – its remittances are equivalent to 8.5% of GDP, more than tourism – and it also serves to provide an outlet for unemployed and dissatisfied youth. The repression in the Rif, which began in May 2017, consisted not only of imprisoning the ringleaders – the four most prominent are still in prison – but also of turning a blind eye to those who were clandestinely heading to Spain.

As they have been extracting concessions, the Moroccan authorities and their local lobbies have become emboldened to the point of what might appear to be meddling in the political and cultural life of their European neighbours. In France, for example, they managed to cancel, in March 2019, the concert of the Sahrawi singer Aziza Brahim at the Arab World Institute, despite the fact that all the tickets were already sold.

Later at least, President Emmanuel Macron was angry with King Mohamed VI when he learned, in July 2021, that he and much of his government had been spied on by the Moroccan secret services with the malicious program Pegasus. The Moroccan writer Tahar Ben Jelloun, very close to the royal palace, narrated the three telephone conversations – three fights – between Macron and the monarch who denied everything. “He disrespected her,” said the novelist.

Yet President Sánchez and at least three of his ministers were also spied on with the same program and the Spanish Government even denounced it in the National Court. But then he did not provide any support to the investigating magistrate, José Luis Calama, when he tried, on two occasions, to carry out a commission in Israel, the country where Pegasus is manufactured. Calama complained about this in the order with which, in July 2014, he provisionally archived the investigation.

In those institutions in Spain that depend on Foreign Affairs or Defense or in which these ministries exert some influence, Morocco has established, in practice, preventive censorship. Its monarchy, the Rif, the conflict in Western Sahara, the arms race with Algeria, etc., are taboo topics that are never addressed in round tables or debates. This is the case, for example, at Casa Arabe in Madrid, at the Elcano Royal Institute (think-tank), at the European Institute of the Mediterranean in Barcelona, at the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies…

It is not that there was an agreement between both governments that these delicate issues were excluded from the agenda, rather that it is that these institutions consider that they should be ignored so as not to upset the authorities of the neighboring country. When, by accident, one of them crosses the red line, then the Moroccan lobby or diplomats intervene to try to silence it. It happened, for the last time, on May 23, at the Euro-Arab Foundation of Granada, where a conference on the Sahara and Palestine “faced multiple obstacles,” according to the Sahrawi Taufiq Moulay in El Independiente.

Self-censorship extends to public media. RTVE has vetoed coverage by its journalists of activities in the Sahrawi refugee camps. Public television in Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Belgium have, however, broadcast reports on Mohamed VI or investigative work on Moroccan interference in the internal affairs of their countries. French public radio even participated in the collective journalistic investigation into Pegasus, which came to light in July 2021, and broadcast its results on the air. Their podcasts are online. Can you imagine something similar in Spain?

Of course, a media freedom law is necessary, like the one announced by President Sánchez. Thus, Spanish public media will be able to follow the example of those in the rest of Europe.

The author is a respected foreign affairs journalist who covers Morocco for some years. His views in this piece, which was originally published in Spanish on the ElConfidencial website, do not necessarily reflect those of Maghrebi.

Want to chase the pulse of North Africa?

Subscribe to receive our FREE weekly PDF magazine