Raphael Machado: Could Russia resolve Western Sahara?

Since the withdrawal of Spanish forces from Western Sahara, the Sahrawis have found themselves in a permanent and ruinous conflict with the Kingdom of Morocco, which claims the territory despite the lack of historical or ethnocultural ties to the region. This conflict, which has alternated between periods of armed struggle and ceasefire, revolves around the recognition or rejection of the independence of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), or the territory’s belonging to Morocco.

Despite the obscurity of this conflict (at least in comparison to more well-known national causes like the Palestinian one), 82 countries already recognize the sovereignty of the SADR, which is also a member of the African Union. In this regard, there is indeed reasonableness in the Sahrawi claim, making their goal plausible in the long term—especially after the global restructuring towards a multipolar order.

READ: Russia’s Stance on Western Sahara and Algeria

This “reasonableness” has been recognized in the international legal sphere since the very beginning of the independence struggle, which took place in the context of decolonization processes. As early as 1975, even before the Spanish withdrawal, the UN demanded the holding of a referendum to decide the fate of the territory. When Morocco referred the issue of Western Sahara and its alleged “ties” to the kingdom to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the verdict concluded that Western Sahara had its own legitimate tribal authorities who had agreed with the King of Spain in the 19th century for annexation, dismissing Morocco’s thesis that the region was “no man’s land” and also denying the existence of any legal ties with Morocco that could override the principle of the Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination.

structural changes in the international arena will make it difficult for Morocco’s claims to continue. The U.S. is losing the ability to project its influence effectively due to the multiplication of its international engagements and the internal process of decline it is undergoing.

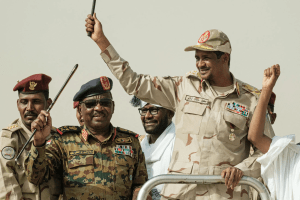

Nevertheless, taking advantage of the power vacuum, Morocco invaded Western Sahara immediately after the ICJ’s ruling. It was a peculiar invasion because there was a strong consensus on the legitimacy of the Sahrawi sovereignty claim, as evidenced particularly in African diplomatic relations, where the SADR enjoys broad support. Morocco was even excluded from the African Union for a long time due to the inclusion of the SADR.

READ: Yasmine Hasnaoui: How Algeria swindles its citizens over the Sahara

Despite promises of a referendum in the early 1990s and the illegal construction of a wall dividing the region into a Morocco-controlled area and a free zone, the reality is that a definitive solution to the conflict remains pending, without an independence referendum, with a small and timid UN mission (MINURSO) compared to others, and with the conflict reignited in recent years.

The United States, as the hegemon in the unipolar order, has already shown it is not interested in a definitive solution to the conflict—at least not one that satisfies the Sahrawis—and supports Morocco’s claims (as does Israel). However, amid the geopolitical transformations accompanying the transition from a unipolar to a multipolar world order, a solution—one already demanded by the UN—may be found for the Western Sahara conflict. In this regard, it is worth noting that countries like Russia and China have experience in resolving conflicts and bringing together geopolitical adversaries, as seen in recent years with the rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia and the renewal of dialogue between Syria and Turkey.

READ: Sarah Leah Whitson: The price of France’s shift on Western Sahara

First and foremost, it is necessary to point out that structural changes in the international arena will make it difficult for Morocco’s claims to continue. The U.S. is losing the ability to project its influence effectively due to the multiplication of its international engagements and the internal process of decline it is undergoing.

Meanwhile, despite the obstacles represented by sanctions, following a possible (favorable to Russia) conclusion of the special military operation, Moscow will be in a position of global influence as high as it enjoyed during the Cold War. The same can be said of Morocco’s other major ally, Israel, which is facing an unprecedented crisis due to its disastrous military campaigns against Gaza and Lebanon. The country is suffering from an exodus, an economic collapse, and diplomatic devastation, with little chance of a quick recovery, even if the conflict ends abruptly.

Morocco is likely to find itself in a situation where it can no longer rely on its main allies. Meanwhile, its main regional rival, Algeria (the principal supporter of the Sahrawi cause), enjoys more favorable international relations in this context, maintaining closer ties with counter-hegemonic powers. Similarly, examining the balance of power further south, in the Sahel, a confederation of states allied with Russia (Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger) is emerging, reinforcing the perception that Moscow will have an increasing role as a mediator in regional conflicts.

Nevertheless, it is important to reiterate that Russia has good relations with Morocco and seeks to enhance them, especially in economic terms, while simultaneously supporting the Sahrawis’ right to self-determination. Thus, Moscow represents a neutral pole, capable of helping mediate this conflict.

In this regard, we can also point to Russia’s experience with the problem of eastern Ukraine, which dragged on from the Maidan in 2013 to the special military operation. Despite numerous differences and peculiarities, both situations involve disputes over the autonomy rights of a “local ethnic identity” against a repressive central power.

During the eight years of asymmetric conflict that preceded the special military operation, the fate of Donbass was debated among various possibilities: forced reintegration into Ukraine without autonomy, consensual reintegration with autonomy, independence, or integration into Russia. Russia favored consensual reintegration with autonomy, a stance reflected in the (failed) Minsk Agreements.

However, considering that Western Sahara was only under Moroccan rule during the (historically) brief Almoravid dynasty and that in other historical periods, the ties between the nomadic tribes of northern present-day Western Sahara and the Maghreb power centers were intermittent, partial, and superficial—unlike the deep and permanent relations between Ukrainian territories and Russian statehood—integration into Morocco appears immediately unreasonable.

With its experience in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, Russia can help organize the necessary referendum to definitively resolve this conflict—and it can help convince Morocco to accept the results. For Russia, this solution is the only one that can enable harmonious integration between the Maghreb and West Africa, restoring ties between Morocco and Algeria, and facilitating the realization of numerous logistical projects, not only Russian but also Chinese, ranging from highways and railways to gas pipelines.

The author is a publisher, geopolitical and political analyst, writer specialized in Latin American affairs. This article was originally published on the website of Strategic Culture Foundation. The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of Maghrebi.org

Want to chase the pulse of North Africa?

Subscribe to receive our FREE weekly PDF magazine