Andreas Krieg: The UAE and secessionist influence in Africa

From North Africa to the Gulf, the UAE has aggressively expanded its counter-revolutionary strategy in the wake of the Arab Spring.

Earlier this month, Sudan’s government brought proceedings against the United Arab Emirates, accusing it of “complicity in genocide” in the Sudanese civil war.

The case sheds light on the Abu Dhabi network providing lethal and financial support to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a violent non-state actor fighting Sudan’s government in a bloody civil war.

The RSF is but one of the nodes in a network of non-state actors the UAE has curated over the past decade. The small Gulf monarchy has tapped into secessionist causes from Libya, to Yemen, Sudan and Somalia, using surrogates as Trojan horses to generate strategic depth and influence.

Like Iran’s “axis of resistance” – a network of non-state actors loosely tied together under an Islamic revolutionary banner – the UAE’s “axis of secessionists” comprises a network of non-state actors tied together under a counterrevolutionary banner. Like Tehran, Abu Dhabi has curated a multilayered network of violent non-state actors, financiers, traders, political figureheads and influencers to create bridgeheads in countries of strategic value to Emirati national interests.

Paradoxically, yearning for a strong state, Abu Dhabi’s ruling elite has created a network of strongmen whose reliance on armed violence has done more to destabilise central governments and undermine state sovereignty across the region.

As a small hydrocarbon state of just one million citizens (and millions more expat residents), the UAE has traditionally been forced to delegate statecraft to surrogates to fill capacity gaps. When foreign and security policy ambitions started to expand during the Arab Spring, so too did the Emirati need for ways to project influence overseas with a minimal footprint.

Abu Dhabi was looking for an effective means to translate petrodollars into geopolitical influence. Ironically, it was the fear of revolutionary non-state actors in 2011 that triggered the UAE to more assertively seek surrogates through which it could contain revolutionaries threatening to overthrow Arab autocrats from North Africa to the Levant and the Gulf.

“When it became clear that their surrogates were unable to seize central government, the UAE was happy to play a game of divide and conquer.”

Most of all, Abu Dhabi wanted to contain and undermine the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist non-state actors that appeared to be best organised to shape the post-revolutionary order.

The Bani Fatima

In a federation of seven emirates, Abu Dhabi and its ruling Al Nahyan family quickly developed into the main hub in a tribal monarchy. Ever since the financial crisis of 2008, the near-bankruptcy of the emirate of Dubai and the subsequent cash injection from oil-rich Abu Dhabi, power has increasingly centralised in the hands of three brothers: Mohammed, Mansour and Tahnoon bin Zayed.

Under their leadership, Abu Dhabi grew into the financial hub of the Emirates. They built a network of corporate and state-owned enterprises that would deliver everything Emirati statecraft required.

The three brothers – dubbed the Bani Fatima – created a parallel infrastructure to deliver strategic investments and financial services. They tied logistics and commodity trading companies, as well as private military and security firms, to the newly developing centre of power.

Beyond geo-economics, the Bani Fatima succeeded in curating webs of private and semi-private entities to connect with sociopolitical and economic shapers in the region. While Abu Dhabi appears to be quite hierarchical internally, a more horizontal core-periphery dynamic thus emerged, with networks of individuals, companies and governmental organisations revolving around the Bani Fatima and their close advisers as the hub of these networks.

What commenced as a war against Islamic civil society and Islamist non-state actors under the pretext of fighting “terrorism” in the Arab Spring developed into a grand strategy of weaponised interdependence. After successfully conspiring with the Egyptian military in 2013 to stage a coup to oust the only democratically elected president in Egypt’s history, Abu Dhabi gained the confidence to use its networks to remake the socio-politics of the region.

The overall vision for President Mohammed bin Zayed and his brothers has become one of strategically entangling elites across the Middle East and Africa into the UAE’s hub. What China is playing as a game of geo-economics, whereby countries develop a co-dependence on Chinese investments and trading power, the UAE has expanded into a geo-strategic space where warlords, criminal smuggling networks, traders and financiers develop a dependency on UAE infrastructure. In return, Abu Dhabi can use its influence to gain strategic depth in countries relevant to core Emirati interests.

Where the Emirati ministries of defence or foreign affairs lack capacity to generate strategic depth, surrogates – mostly in the private sector in countries of interest – can fill the gap. The influence Abu Dhabi generates can be traded with the United States, Russia or China in return for great power protection and relevance.

Diverse networks

Secessionist or insurgency causes in unstable states inevitably build coherent networks that are embedded in local communities. Like Iran’s cultivation of armed non-state actors tied to communal – mostly Shia resistance – causes, the UAE found that communities with a strong cause are best suited to host armed non-state actors.

When it became clear that their surrogates were unable to seize central government, the UAE was happy to play a game of divide and conquer. In Libya, Sudan, Yemen and Somalia, communally based non-state actors have all created alternative claims to territoriality and sovereignty to rival their respective UN-backed central governments.

The networks Abu Dhabi has curated are diverse. Nodes in the networks retain a great degree of autonomy, with the UAE content to surrender some control over activities on the ground. Connections between the various networks tend to be horizontal rather than vertical, where Abu Dhabi often remains the switch to orchestrate and connect different nodes from different networks.

While much of the attention on the UAE’s axis of secessionists focuses on militarised non-state actors – such as the Libyan National Army (LNA), the RSF in Sudan, the Security Belt Forces (SBF) in Yemen, or the Somaliland Armed Forces and Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF) in Somalia – there is an extensive underbelly of financial, logistics, trade and information networks that keep them afloat.

The security networks of armed militias, rebels and mercenaries are supported by networks of logisticians and commodity traders. In addition, financial networks allow surrogates to exchange commodities and minerals for more fungible assets.

Financial networks also provide surrogates with the means to bypass sanctions and purchase goods, services and arms in the UAE to support their ventures. UAE-based logistics companies provide a range of vehicles to ship material support and arms to and around countries of destination. Information networks of influencers, media companies and spin doctors generate the necessary narratives to whitewash in-country operations.

The Libya experiment

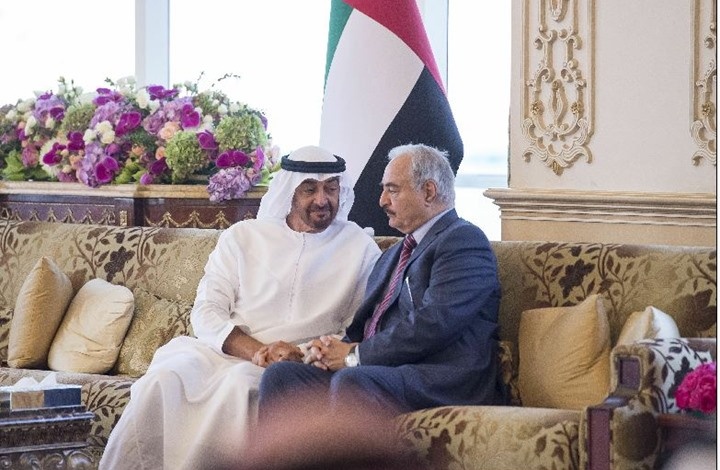

The roots of the Emirati axis of secessionists go back to 2014. A former commander of Muammar Gaddafi’s army, Khalifa Haftar, had recently returned to Libya from exile.

In February 2014, he unsuccessfully tried to launch a counterrevolution on YouTube, and Abu Dhabi took notice. Within three months, Emirati money, military and information support reshaped the warlord’s YouTube revolution into a full-scale counterrevolutionary effort, under the banner of fighting “terrorism”.

Operation Dignity was conducted by a network of disenfranchised militias and brigades against the Emirati scarecrow of the “Muslim Brotherhood” – a catch-all bogeyman describing all revolutionary forces that toppled Gaddafi in 2011. Their attack on the Libyan parliament in May 2014 forged the LNA, an oxymoronic web of militias that is neither inclusively national, nor an army in the traditional sense.

While Operation Dignity failed to completely undo the achievements of the revolution, Haftar nonetheless succeeded in capturing eastern Libya, with Benghazi as its capital. Attempts by the LNA, with Emirati and Russian support, to topple the UN-backed government in Tripoli consecutively failed – but this did not stop the LNA from building its own sociopolitical infrastructure rivalling that of the central government.

Today, the LNA is a militia network with a quasi-state. At its helm is an ageing strongman whose family has created a system of patronage in Benghazi that will ensure regime longevity. More importantly, the UAE has been able to revive the traditional “eastern cause” of tribes in eastern Libya.

The LNA’s sphere of influence neatly fits the boundaries of Libya’s traditional region of Cyrenaica, which sees itself as socio-culturally separate from western Libya’s Tripolitania and the southern Fezzan.

The security networks fuelling the LNA over the years were transnational. The LNA’s activities became a major gateway for African mercenaries, as Russian and Saharan soldiers of fortune became essential force multipliers for Libyan militia brigades.

Libya thus emerged as a bridgehead for the UAE’s regional security networks. Military bases were used to supply fighters with material and lethal support, and a carousel of guns-for-hire spun out of the LNA’s war into other conflicts in the region.

Emirati advisers on the ground were involved in training and providing intelligence support to the LNA, while the UAE on multiple occasions delivered air support. When in 2019, Russia’s Wagner network set up shop in Libya – allegedly paid by UAE banks – the LNA’s hub position in a continental security network was fully established.

Haftar was able to provide Russia with a platform from which to launch operations across the continent. Russian planes could land on LNA-seized military bases and fly onward to other conflict zones in the region.

A key asset was a network of logisticians and private logistics companies, often based in the UAE, that would provide strategic airlift capability. Fighters, material support and arms had to be flown not just into Libya, but onward to other war zones.

The supply chain of the UAE’s security network has been widely privatised to achieve plausible deniability. In 2020, at the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the UAE airforce relied on Emirati companies to drop 150 cargo planeloads of arms into Libya – an arsenal that still feeds fighters across the network today.

Abu Dhabi has also provided financial networks to assist with the funding of LNA operations. Billions of dollars in frozen Gaddafi assets were allegedly released from Emirati banks to eastern Libya to fund Haftar’s endeavours.

In addition, LNA authorities tried to sell Libyan oil from seized oil fields behind the back of the National Oil Company through a rival firm, and to deposit receipts in Emirati banks – but commodity traders were nervous to bypass Libya’s state oil company, shifting the illegal sales to the black market. Still, reports suggest that Haftar’s family at least has been able to bank privately in the UAE.

Coming of age in Yemen

Amid the LNA’s consolidation of power in Libya, the UAE was called upon by Saudi Arabia in March 2015 to support its war against the Houthis in Yemen. For Abu Dhabi, Yemen offered an opportunity to develop strategic depth in the southern coastal areas, with Aden and the Bab al-Mandab Strait as one of the world’s key maritime chokepoints.

Not only was Abu Dhabi able to continue its war against “terrorism” – including both jihadist networks and Islamist civil society groups and politicians – but it could also expand (and later weaponise) its web of interdependence.

The UAE executed a range of military operations to secure Yemen’s coastal areas, but after a Houthi missile struck an Emirati base in Marib in September 2015, killing 52 soldiers, Abu Dhabi rethought its strategy. The deadliest attack in the history of the UAE’s armed forces prompted it to limit the exposure of its troops, and increasingly delegate fighting to contractors and mercenaries.

In 2016, the Emiratis established the Security Belt Forces (SBF), a paramilitary force built from a conglomerate of tribal fighters in southern Yemen. With this and the political umbrella of the Southern Transitional Council (STC), established the following year, Abu Dhabi increasingly divorced its Yemen policy from the original Saudi-led campaign.

Realising that the highly polarised and divided sociopolitical realities of Yemen could not be controlled, the UAE resorted to a divide-and-rule approach, similar to the one in Libya. The STC would be established atop the existing southern secessionist cause.

The Southern Movement was the best organised, with a clear narrative built around independence from Yemen’s north, and a ready-made tribal network of brigades that could bring armed force to bear at a low cost for the Emiratis. A general from the SBF, Aidarus al-Zoubaidi, was appointed to helm the STC – quite unlike Haftar, although far less suited to play the role of military strongman.

Despite marketing itself as a united southern front, the STC remains largely a network of brigades whose commanders operate with extensive autonomy from any central leadership, acting more like warlords with their own armies and law enforcers tied to them personally. Like Libya’s LNA, command and control in the UAE’s security network in Yemen is widely decentralised.

As Yemen’s north plunged into more chaos, the UAE tried to consolidate influence under the banner of the STC in the south. In 2019, STC-aligned militias seized the presidential palace in Aden, depriving the already exiled UN-backed government of its local residence.

The Riyadh Agreement of 2019, though marketed as a reconciliation between the central government and the separatists, elevated the STC to a position of international legitimacy. Abu Dhabi has since lent its diplomatic and political clout to the STC, introducing Zoubaidi to its partners in Russia, where he speaks as the legitimate representative of Yemen.

Emirati financial and trading networks create the wiring to support the STC materially and financially. The territories held by the STC are economically lucrative, with the coastal areas – Aden in particular – offering access to the most important maritime shipping routes in the world.

After the Dubai-based DP World’s contract to manage Aden’s port was terminated in 2012, as of last year, the Abu Dhabi-based AD Ports was reportedly negotiating to resume port management. Such a deal would grant the state-owned Emirati company control of a strategically critical trading post, while generating revenues for the STC.

Furthermore, the STC’s control enables Emirati companies to access the energy infrastructure in Balhaf and oil fields in Masila. Southern Yemen’s crown jewels are thus offered to Emirati entities. Networks of UAE-based commodity traders arrange for oil to be smuggled from Yemen and sold on the global market, with some profits likely pocketed by the STC administration. The UAE brings investments to STC-held territories, in return for Emirati access to critical national infrastructure.

Pulling strings in Sudan

Sudanese fighters have been part of the Emirati web of networks from the outset. Sudanese fighters supported the LNA in Libya, and the RSF under warlord Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemeti, sent thousands of men to fight for the UAE in the war in Yemen.

RSF guns-for-hire became a lucrative source of income for Hemeti in supporting the Saudi-Emirati war against the Houthis. Drawn from tribes in the border region between Sudan and Chad in the conflict-ridden region of Darfur, the RSF was built on a separatist cause fuelled since the 1980s.

Used as a praetorian guard by former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, the RSF has developed into a state within a state since its formal creation in 2013. The immense wealth that Hemeti and his family were able to accumulate, through gold trade and smuggling, ensured the RSF’s financial independence. Using the UAE as a hub to sell Sudanese gold – both legally and illicitly mined – they have accumulated wealth in Emirati banks.

In 2018, the outbreak of the Sudanese revolution against long-standing strongman Bashir plunged the country into instability. A military coup by the Sudanese army in 2019 was supported by the RSF, unleashing a struggle for power in Khartoum.

For Abu Dhabi, this was a chance to do away with the Islamist-leaning Bashir regime and get access to an important crossroads in eastern Africa. But Emirati and Saudi funding was unable to contain the power struggle, which escalated into a full-scale civil war by 2023, pitting the RSF against the Sudanese military.

Hemeti presented an opportunity for Abu Dhabi to back another military strongman with financial entanglements in the UAE – one whose militia network had a strong separatist cause.

Darfurian tribal fighters had already made a name for themselves in Gaddafi’s war against Chad in the 1980s – a campaign led on the Libyan side by none other than Haftar. Since RSF fighters had already supplemented the LNA and supported the STC-aligned security networks, it is not surprising that both Libya and Yemen became sources of material and military support to the RSF. Returning fighters have brought back arms and munitions.

In addition, the LNA’s arms depots were restocked by the UAE in 2020, enabling Haftar to resupply his partners in Sudan with Emirati weapons, while granting Abu Dhabi plausible deniability.

As the war in Sudan intensified, the RSF needed more small arms, missiles, mortars and drones. Abu Dhabi has been using innovative ways to conceal illegal shipmentsof arms under the guise of humanitarian aid, using UAE-based logistics companies to fly them into Chad and Uganda, from where they are either flown onward or driven across the border to Darfur.

Parts of the network are almost self-funding. The Hemeti family’s network of mines, commodity traders, front companies and bank accounts all coalesce in the UAE, which has become the financial haven for the RSF’s gold business. Gold is mined in RSF-held territories, flown to Dubai, exchanged for cash, and stored in Emirati banks. That money can pay salaries, charter air cargo flights, buy weapons and vehicles, and hire PR companies or Russian mercenaries.

The US Treasury has sanctioned a range of UAE-based companies – some fronting for the Hemeti family to purchase supplies for the RSF, others providing the logistics to fly supplies and Wagner mercenaries into Sudan. Abu Dhabi has provided this network with the necessary infrastructure to create a value chain, from the raw gold in the ground to arms being delivered to fighters on the RSF front lines.

Emirati information networks, meanwhile, offer Hemeti opportunities to polish his image. Amid increasing media pressure on the RSF over atrocities committed in Sudan – including accusations of genocide – Hemeti has relied on UAE-based PR companies to polish his image and give the RSF a veneer of legitimacy.

Abu Dhabi’s broad global network of public relations specialists and media consultants have tried to transform the image of the militia network into a sophisticated alternative to the UN-backed government. These efforts have been undermined, however, by the newly filed genocide case at the International Court of Justice.

Divide and rule in Somalia

Somalia is the physical manifestation of the Horn of Africa. Its immense strategic value to global shipping routes and trade corridors into the African hinterland put the country on the UAE’s radar as far back as 2010.

For Abu Dhabi, Somalia has been a key focal point in its policy to generate interconnectivity and weaponised interdependence. For state-owned logistics giants DP World and AD Ports, it offers ideal locations for transshipment hubs.

But bilateral relations between Abu Dhabi and the federal government in Mogadishu have had their ups and downs, making it an unreliable avenue to generate Emirati influence. The UAE has thus resorted to a policy of bypassing Mogadishu to engage directly with various states, especially those with a separatist agenda.

In 2010, the UAE set up a force of mercenaries in the region of Puntland to hunt down pirates on land and sea. The Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF) was initially run by a UAE-based company, in violation of a UN arms embargo, and reported directly to the Puntland president, bypassing the sovereignty of the Somali federal government. The UAE has paid salaries and in 2022 opened a military base in Bosaso, which has become a node in the resupply network of the RSF in Sudan.

“Held together by the prospect of political autonomy from a central government, a profiteering motive, and access to the UAE’s exceptional financial and logistical infrastructure, the axis of secessionists has emerged as a resilient network across an important geo-strategic space.”

Since 2017, the UAE has also expanded its engagement with Somaliland, arguably the autonomous region with the strongest independence movement within the Somali federation. To strengthen its claim to autonomy, the Somaliland government accepted an Emirati bid to establish a military base in Berbera, an important geo-strategic location in the Gulf of Aden.

Abu Dhabi has also been training Somaliland forces to further separate the region’s security sector from the federal government in Mogadishu. Today, the UAE is the most important investor in Somaliland, and it is likely behind an effort to lobby the Trump administration to recognise the state as an independent nation in return for basing rights.

Since 2023, Abu Dhabi has also increased its footprint in Jubaland, strengthening the southern Somali region’s separatist claim at a time of heightened tensions with Mogadishu. The UAE has conducted drone strikes and provided military vehicles to Jubaland state forces. Jubaland leader Ahmed Madobe maintains intimate ties with Abu Dhabi, and has allowed the Emiratis to build a military base in the regional capital of Kismayo.

Upon realising that Mogadishu’s federal government did not want to put all its eggs in the Emirati basket, Abu Dhabi strategically diversified its approach in Somalia. Rather than going after the primary centre of power, the UAE decentralised its approach, going after alternative centres of power where it could guarantee a monopoly of patronage – at the expense of Somalia’s territorial integrity.

Indispensable broker

The UAE’s support for the RSF is just one piece of a much wider networked puzzle, which aims to generate strategic depth through a web of intermediaries. Abu Dhabi has established itself as a hub in a regional network that not only augments the UAE’s limited capacity and status, but creates an organic, self-sustaining system of interdependence, where nodes operate with degrees of autonomy that in turn provide the UAE with plausible deniability.

The value chain that Abu Dhabi has created across the region cannot be divorced from the UAE as a jurisdiction, but is maintained by an assemblage of state and corporate actors that do not directly feature the Bani Fatima.

Held together by the prospect of political autonomy from a central government, a profiteering motive, and access to the UAE’s exceptional financial and logistical infrastructure, the axis of secessionists has emerged as a resilient network across an important geo-strategic space.

Both middle and great powers cannot avoid engaging with Abu Dhabi in these jurisdictions, elevating the UAE’s global status to that of an indispensable broker – one that is able to pit one interest against another, while securing strategic bridgeheads for itself.

Russia’s mercenary and commodity-profiteering network of the Africa Corp, formerly known as Wagner – relies on the axis of secessionists to get in and out of Africa. China’s hunger for resources requires secure supply chains across the African continent, and Beijing will find it hard to avoid key chokepoints that are now under direct or indirect Emirati influence. The Trump administration, meanwhile, is also entering the game of geo-economics, tapping into the connections Abu Dhabi has generated.

READ: French occupation of Algeria mirrors Israel-Gaza genocide

Through this axis, the traditional, small state of the UAE has been elevated to a regional great power, achieving far more effective levels of entanglement and interdependence than its larger neighbour Saudi Arabia, or its agile neighbour Qatar. For Abu Dhabi, this network has become the bedrock of strategic autonomy to pursue its own interests – even when at odds with western interests and values.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Maghrebi.org. Dr. Andreas Krieg is an associate professor at the Defence Studies Department of King’s College London and a strategic risk consultant working for governmental and commercial clients in the Middle East. He recently published a book called ‘Socio-political order and security in the Arab World’.

If you wish to pitch an opinion piece please send your article to alisa.butterwick@maghrebi.org.

Want to chase the pulse of North Africa?

Subscribe to receive our FREE weekly PDF magazine