Daniel Haile: Russia’s bases in Africa are a strategic foothold for expansion

Russia’s naval base in Sudan, situated on the Red Sea, is a calculated geopolitical and geoeconomic move designed to secure a long-term military foothold along one of the world’s most critical maritime trade routes. This corridor links Africa, Europe, and the Middle East and serves as a strategic gateway to expand Russian soft and hard power into the Sahel and Africa’s hinterland.

Insecurity Is a Window of Opportunity

Moscow’s economic and military interests in the Horn of Africa are resurging in a manner reminiscent of the Soviet era. During the Cold War, the Kremlin initially supported the regime of Siad Barre in Somalia before switching sides to back Ethiopia’s communist Derg regime under Mengistu Haile Mariam, a Marxist government responsible for the Red Terror and the deaths of more than 500,000 people. Russia’s current approach follows a similar pattern of pragmatic realignment.

Sudan’s ongoing civil war is a power struggle between General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as “Hemedti,” who leads the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The conflict has been fueled by both regional and foreign actors competing for influence over Sudan’s geostrategic position and resource wealth. With 35 coups since 1956, Sudan has remained politically volatile, an environment ripe for foreign intervention.

Through the Wagner Group, Moscow covertly supported Hemedti for years, leveraging Sudan’s illicit gold trade to fund both sides’ interests while evading international sanctions. In return, Wagner provided weapons, ammunition, aviation assets, and fuel, significantly enhancing the RSF’s battlefield capabilities. Russia’s ambitions in Sudan go beyond resource exploitation. The primary objective is to establish a permanent naval presence on the Red Sea. Following Yevgeny Prigozhin’s death, Moscow reassessed its strategic calculus.

As the SAF gained momentum on the battlefield, systematically degrading the RSF’s decentralized military structure, Russia recalibrated its strategy, aligning more closely with Burhan’s forces. This shift in tactical alignment reflects Russia’s pursuit of strategic real estate along the Red Sea. With growing backing from Iran, Egypt, Eritrea, and Saudi Arabia for Burhan, Russia’s repositioning from the RSF to the SAF marks a tactical realignment in pursuit of long-term access. The naval base in Sudan is not merely a point of military presence but a forward operating base for Russian expansion into Africa.

The United Arab Emirates and Libya have emerged as the RSF’s chief external backers, providing military aid, financial support, and political cover. In contrast, Qatar has remained largely neutral, attempting to mediate rather than escalate. The SAF has launched a case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), accusing the UAE of complicity in war crimes and genocide committed by the RSF. The legal case underscores the deepening polarization of the conflict, elevating it from a domestic power struggle to a regional proxy war with grave humanitarian consequences. The RSF, born from the Janjaweed militiaresponsible for atrocities and genocide in Darfur, continues to carry out the brutal legacy of its origins, now emboldened by military support from foreign backers.

From Port Sudan to the Sahel

As instability across the Sahel and West Africa intensifies, Moscow’s military and political footprint on the continent is poised to grow. Russia’s strategic interests in Africa lie in exploiting gray zones, regions plagued by weak governance, competing power centers, fractured sovereignty, and the absence of a monopoly on violence. Despite a constrained and weak economic power, Moscow has skillfully leveraged both hard and soft power to entrench its influence in Libya, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali.

Where insecurity prevails, a monopoly on violence is absent, and factions compete for control of state resources, Russia sees opportunity. Sudan is a carbon copy of Libya in these respects: fragmented authority, competing armed factions, and a vulnerable geostrategic position ripe for meddling from regional and international actors. Moscow thrives in these vacuums, where formal institutions collapse, and external actors can establish long-term footholds through either military partnerships or paramilitary proxies.

Russia’s presence in Africa, whether through official military agreements or via its surrogates, such as the Africa Corps (formerly the Wagner Group), is reshaping the continent’s geopolitical landscape. As Washington continues its strategic retrenchment, a rapprochement is accelerating between African governments and Moscow. Russia is effectively exploiting anti-colonial sentiment across the continent, drawing on the Soviet Union’s historical support for African liberation movements as a point of ideological alignment.

Modern-day Russia has inherited the diplomatic capital built by the USSR in Africa. Washington’s retrenchment from Africa will only accelerate a geopolitical realignment. As Europe continues to grapple with its colonial legacy, Russia exploits the narrative that Moscow, unlike the West, supported African liberation movements. This message resonates, particularly in regions where the Soviet Union historically provided financial and military backing to anti-colonial forces.

“Without renewed political, economic, and security engagement, Africa, the world’s second-largest continent, may soon fall under the sustained influence of America’s geopolitical rivals. Moscow capitalizes on the ambiguity of contested spaces, offering security assistance, resource partnerships, and ideological alignment wherever Washington retreats or hesitates.”

Moscow continues to benefit from this legacy, having inherited deep diplomatic ties forged during the Cold War. The establishment of institutions such as Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow served both educational and ideological purposes, shaping generations of African leaders. Today, the fallout from NATO’s intervention in Libya and growing anti-French sentiment, fueled by decades of economic exploitation, provide fertile ground for Russia’s ideological subversion. By leveraging these historic grievances, Moscow positions itself as a reliable partner, particularly in contrast to a retreating Washington.

Recalibrating American Strategy in Africa

Washington must recalibrate its foreign policy and adopt a leadership strategy grounded in strategic clarity. This recalibration demands prioritizing security and economic development over the idealistic and often impractical pursuit of human rights. The United States must shift its focus toward forging strategic partnerships anchored in mutual interests, regional stability, and long-term security cooperation.

Moscow and Beijing understand a fundamental truth: it is both naive and strategically flawed to assume that all nations can adopt democratic systems or that their populations will inherently embrace Western political models. Russia’s approach to Africa is rooted in pragmatism, leveraging governance vacuums and regional instability to advance its strategic objectives. While Washington remains tethered to the belief that liberal democracy is a universal aspiration, Moscow recognizes that many African states are more immediately concerned with internal security, economic development, and the sovereign right to determine their own political futures. Unencumbered by ideological rigidity, Russia forges alliances that serve its long-term interests, regardless of regime type.

If Washington is willing to partner with Islamist regimes and absolute monarchies across the Middle East, it must ask why African strongmen are treated any differently. The nature of governance, whether in North Africa or sub-Saharan Africa, should not preclude strategic alignment when mutual interests are at stake. If African nations aspire to democratic governance, they must be willing to build it, defend it, and, if necessary, fight for it. Democracy is not an exportable commodity; it must be forged from within, through the consent and will of the people to embrace democratic values and norms.

The United States does not carry the burden of Europe’s colonial legacy and is uniquely positioned to forge more credible and enduring partnerships across the African continent. Washington’s continued disengagement risks ceding strategic terrain to Russia, China, and a coalition of rising middle powers, most notably Turkey, India, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. Without renewed political, economic, and security engagement, Africa, the world’s second-largest continent, may soon fall under the sustained influence of America’s geopolitical rivals. Moscow capitalizes on the ambiguity of contested spaces, offering security assistance, resource partnerships, and ideological alignment wherever Washington retreats or hesitates.

Port Sudan Is Just the Opening Move

Russia’s naval base on the Red Sea in Sudan, along with its Mediterranean foothold in Libya and the Maaten al-Sarra Air Base in southern Libya near the Sudan–Chad border, provides Moscow with strategic depth and forward operating bases. These installations enhance Russia’s flexibility, particularly in light of the political instability surrounding Syria’s terrorist regime, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), an offshoot of Jabhat al-Nusrah and a disciple of Al-Qaeda. While Russia maintains its presence at Khmeimim Air Base near Latakia and the Tartus Naval Base, its expanding footprint in North Africa reduces dependency on Syria’s unstable real estate, allowing Moscow to capitalize on the geostrategic locations of Sudan and Libya.

The naval base in Sudan provides Moscow with a strategic foothold to safeguard Russian oil and gas investments in conflict-ridden South Sudan while simultaneously expanding its regional influence through the development of refineries and energy infrastructure. By leveraging Port Sudan as a critical economic and logistical hub, Russia is well-positioned to construct a pipeline linking South Sudan’s oil fields to export terminals on the Red Sea, securing vital energy corridors and consolidating its presence across the Horn of Africa. Port Sudan can serve as a vital economic and logistical hub, linking South Sudan’s oil fields directly to Red Sea export terminals, solidifying Russia’s grip on regional energy corridors. Geopolitical influence in Sudan offers Russia an indirect bridge to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, given Sudan’s membership in the Arab League. By embedding itself in Sudan’s strategic calculus, Moscow positions itself closer to the political centers of the Arab world.

The Red Sea is no longer merely a maritime artery; it is a contested battlespace. With eight foreign military bases in Djibouti alone, operated by Germany, Spain, Italy, France, the United States, the United Kingdom, China, and Saudi Arabia, the region’s strategic importance cannot be overstated. The Houthi maritime attacks and the broader proxy conflict in Yemen have further elevated the Red Sea as a critical maritime choke point for global trade. Russia’s foothold in Port Sudan is not an isolated maneuver; it is a strategic offensive maneuver in a broader campaign to project hard power across Africa.

READ: Why Algeria commemorates VE day

Moscow is scripting a new playbook for influence, from the Red Sea to Burkina Faso. If the United States continues to underestimate the geopolitical gravity of Russia’s and China’s economic, political, and military influence, it won’t just lose relevance; it will forfeit access, leverage, and the ability to shape outcomes in a region critical to global trade and security. Egypt’s joint military exercise with China, Eagles of Civilization 2025, should serve as a wake-up call. Moscow is not sitting on the bench waiting to be substituted; it’s already in the game, setting the pace. The era of benign neglect is over. If Washington fails to recognize Russia’s naval base in Port Sudan for what it truly is, a gateway to great-power competition on the African continent, it will one day awaken to find a region not merely lost to Russian influence but strategically recalibrated against American interest

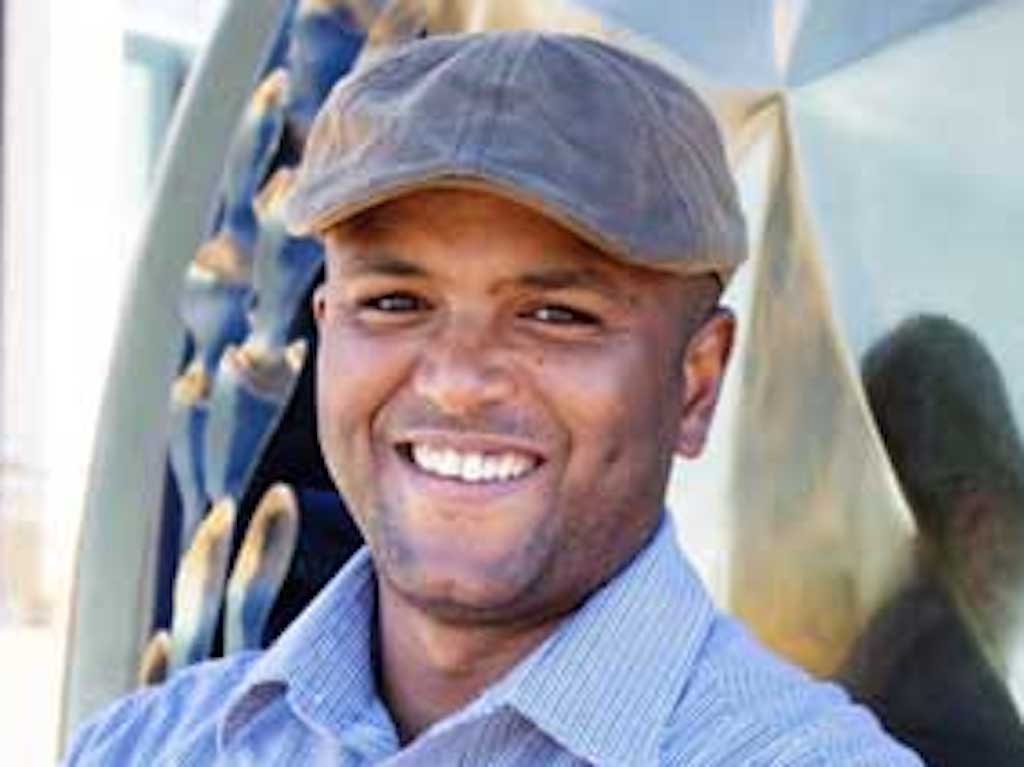

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Maghrebi.org. Daniel Haile is a United States Army Officer with a distinguished academic background, holding two Master’s degrees in International Affairs from Texas A&M University’s Bush School of Government and Public Service and Texas State University. Born in the Horn of Africa, he offers a unique perspective on the region, enriched by personal experiences and extensive research. Daniel’s op-eds have been featured in notable publications, including The National Interest and InDepthNews, where he delivers insightful analyses on African politics. A leading voice on East African geopolitics, Daniel is the host of the Nzuri Kahawa Report Podcast, where he explores the intricate geopolitical and geoeconomic dynamics that are shaping Africa’s rapidly changing landscape.

If you wish to pitch an opinion piece please send your article to alisa.butterwick@maghrebi.org.

Want to chase the pulse of North Africa?

Subscribe to receive our FREE weekly PDF magazine