Explained: Algeria’s complex web of international diplomacy

Straddling continents and geopolitical fault lines, Algerian diplomacy requires more delicacy than ever before.

Economic partnership with the EU stands in direct juxtaposition to its military ties with Russia and the global south.

Losing ground internationally in the Western Sahara dispute and facing upheavals on its southern border with Mali, Algiers looks increasingly isolated.

Intissar Fakir, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute, said: “Algeria is feeling very sort of kind of contained and alienated.”

“They have diplomatic tension with Mali, they’re struggling to deal with the growing recognition of Morocco’s autonomy plan for Western Sahara and they’re uncertain about where they stand vis-a-vis the US administration, particularly with Senator Rubio as Secretary of State. So they are a little bit worried.”

The spigot of Russian weapons flowing into Algeria has also ebbed following the war in Ukraine, muddying the waters of their most central and historic international relationship.

Fighting in northern Mali last year caused great anxiety for Abdelmadjid Tebboune and his regime in Algiers; skirmishing fought by the Russian Wagner group in co-action with Malian government forces.

Tensions peaked this year when Algeria claimed to shoot down a Malian drone which allegedly crossed the border.

Even as the Russian backed junta in Bamako erodes Algiers’ influence via its battling of proxy Tuareg forces in northern Mali, the north African country remains intricately wedded to Moscow.

Fakir said: “Their relationship with Russia is complex, not only because Russia is far away, but also because they have to balance so many different factors in their relationship. They still rely heavily on Russian weapons and Russian arms, so they need to have that relationship be smooth enough to facilitate that kind of access.”

“The US does provide and sell some weapons to Algeria. It’s not a lot, but they do buy from them. And so there’s also that relationship which was threatened when Algeria turned around and bought the SU fighter jets from Russia, just months after signing a memorandum of understanding with the US.”

“Now they’re worried about sanctions, potentially under CAATSA [Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act], here in the US. So it’s a really difficult thing for them to balance.”

At least for now, frosty relations with its former colonial ruler France seem to be on the mend.

Ties fractured after Paris recognised Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara in July 2024, a 50-year-long dispute which still inflames north Africans today.

Diplomats were expelled on both sides in April after France allegedly uncovered a plot to kidnap an Algerian influencer critical of Tebboune’s regime.

Still, with tensions boiling over at a diplomatic level, the only trade sanctions applied were that of Algeria banning imports of French wheat.

“I think we have seen that Algeria is not shy about using all the tools it has in order to make a point diplomatically, and kind of not so diplomatically with the French. I think Algeria is not hesitant about using those tools”, said Fakir.

“France, on the other hand, tries to be a little bit more circumspect, because I think they understand that history is not on their side. They also have to play this issue much more carefully, because for them it also has domestic relevance, with the entire decolonisation process still being a fairly relevant concern for some French voters.”

The descendants of the Peids-Noirs, of which there are 1.3 million in France, who were staunch supporters of French colonial rule in Algeria before independence, still have a loud political voice today.

In 2016, they established the Gouvernement provisoire Pied-Noir en exil (Provisional Government of the Pied-Noir People in Exile) and acquired a 285-hectare plot of land north of Montpellier in southern France.

Fakir said: “The descendants of the Pieds-Noirs that are French and that vote in France, tend to vote very conservative. They tend to be more politically organised and try to compel the French political spectrum to be more hawkish, more kind of aggressive, in their position towards Algeria.

“One of the things that I’m not sure about is this generation of French-born Algerians – the extent to which they actually drive the foreign policy or care about the foreign policy.

“They care about being able to travel back to Algeria, if they have a business and they need to conduct business, or they need to secure visas for their families and so on.”

“Their concerns are more pragmatic and practical than ideological, which, if you were to maybe contrast them to the population of Pieds-Noirs descendants, that tends to be more ideological.”

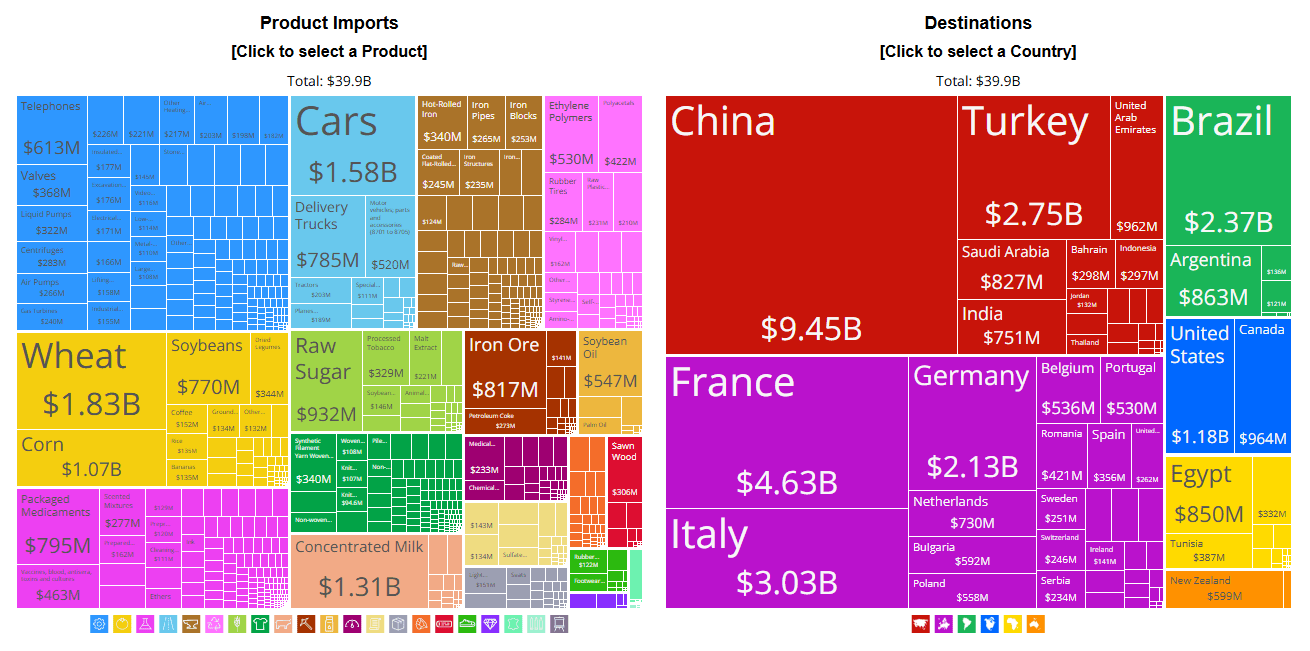

As well as having a diverse array of major import partners, with China, Turkey and Brazil complementing EU trade, this gives Algeria an extra degree of manoeuvrability over France.

However, exports tell a different story, with EU countries making up over 2/3rds of Algeria’s export trade.

Europe is in dire need of Algiers’ crown jewel industry – petroleum and gas – but influence works both ways.

Fakir said: “If Algeria suspends sales of energy to France, then they have to find a buyer or go out and potentially ship the same content to someone farther away for which they would have to pay more in terms of shipping costs and so on.”

“So I think they are going to use the tools at their disposal that are not going to shoot them in the foot.”

As the international order morphs in dramatic ways, catalysed by a Trump presidency, the jury is out on where Algeria will end up.

However, as the embryo of the multipolar world begins to develop, Algeria may present a model for the future – a state outside of the East-West divide, nurturing paradoxical relationships for its own national interest.

BBC, Arab Weekly, Atalayar, MidiLibre.fr, oec.world

Want to chase the pulse of North Africa?

Subscribe to receive our FREE weekly PDF magazine