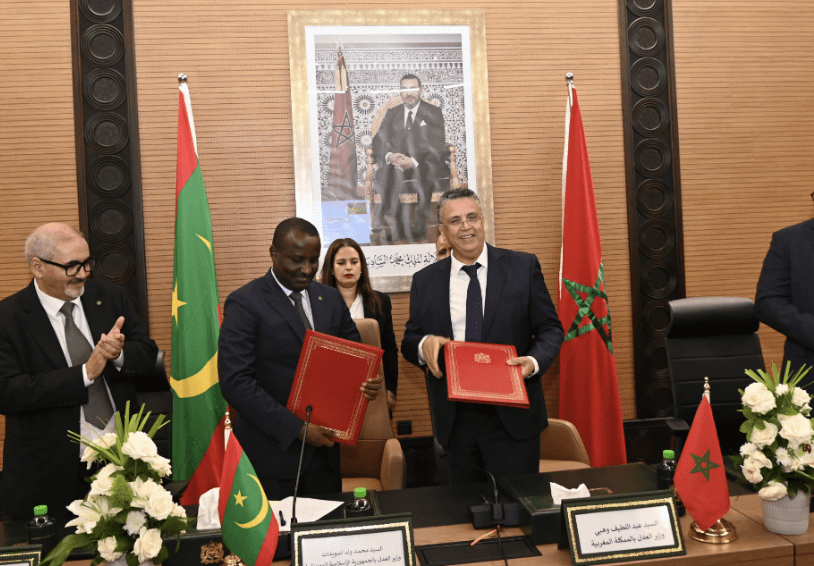

Prison overcrowding: How Morocco plans to fix its broken justice system

According to Daily Liberation, August 24, advocates of justice reform have secured a massive victory in Morocco, as the government passes a bill to offer alternative sentencing for minor offences.

The move follows the successful passage of Law No. 43.22 through parliament.

As well as taking on board the recommendations of human rights bodies, Morocco is also looking to align itself with its own 2013 Charter for Justice Reform and the Meknes Conference on Criminal Policy.

In a country known for political imprisonment and overcrowded prisons, Morocco is exploring other criminal justice methods with proven track records of rehabilitating and reintegrating offenders back into civilian life. Through policies such as community service and targeted rights restrictions, to daily fines and electronic monitoring, Morocco is hoping these reforms will help criminal sentencing to be more socially productive.

Criminologists have long understood the consequences of prison overcrowding and short-term prison sentencing practices. When such facilities become overcrowded, it leads to staff being completely unable to cope with the number of inmates. This causes facilities to be unable to function on the most basic level, failing to provide services from education, healthcare, work and basic expectations of privacy. While short-term prisoners often become hardened, and more reliant on criminal organisations.

Morocco is not an exceptional case either, with the United Nations and Council of Europe recommending the sparing use of prison sentencing to only the most serious cases. To that end, Morocco is looking to implement the policy particularly for crimes with a sentence of less than 5 years, as well as for minors under the age of 18 (with certain exceptions).

The first of the four new sentencing options, community service will have a range of hours (between 40 and 3,600) that judges and prosecutors can levy depending on the severity of the crime. Government bodies, and other approved organisations, will host the programme, with supervisory officers monitoring offenders alongside a standardised register used to track progress.

Electronic monitoring will be determined by a judge, who will approve the duration, authorised locations the wearer can visit and curfew hours. The wearer will be encouraged to respect these terms, with judges being able to convert the punishment into a prison sentence.

Comprising a variety of options that can be rolled out for different offences, targeted rights restrictions will include measures from prohibitions on visiting certain places, mandated therapy, victim compensation and more. The aim is to guide an offender’s behaviour in a positive direction, tailoring the sentence to an individual’s circumstances.

Daily fines follow the principle of replacing the deprivation of liberty that prison provides with a large fine spaced out over time. The payment plan-authorised by a judge based on factors such as income and expenses-will be completed within a 6 month period, similar to the other punishments in these reforms.

This may be an opportunity to improve the justice system in Morocco, but the country must not fall into the same trap so many other countries around the world have done in the past.

These sentences must not become what criminologists term a ‘widening of the net,’ wherein, alternative sentencing measures simply become an additional punishment applied to criminal cases that do not merit the sentence; New sentencing powers must not be added to the list of available sanctions for judges, instead, being strictly used to replace incarceration on specific criminal cases.

Proportional punishments must be administered, especially when it comes to fines as a sentence too harsh could effectively render it a ‘tax’ on impoverished defendants.

Meanwhile, electronic monitoring and community service share similar challenges for implementation: operational capacity. Costs will emerge from different processing requirements to effective training for officers. 24/7 supervision teams will now be needed to track the number of hours worked, breaches in sentencing conditions and quick reaction capabilities to those incidents, as well as ongoing audits of the technical reliability of the new system.

If Morocco wants to turn this into a success story, it needs to be open and honest with citizens to convince them of its efficacy, and to rebuild public trust. Decriminalising certain offences within the justice system is a hugely positive step that should be commended. However, it is a dramatic change that requires resources, partnerships alongside new and continuous training, but most importantly, discipline.

Daily Liberation (Quotidien Libération), Maghrebi.org

Want to chase the pulse of North Africa?

Subscribe to receive our FREE weekly PDF magazine