Satellite data expose major methane leaks in Morocco’s landfill

Credit: Hespress

Satellite data have uncovered unusually high methane emissions from Casablanca’s main landfill in Morocco, reported Nature Journal study and Hespress on 5 November.

A new global study has revealed large uncertainties in estimating methane emissions from waste disposal sites and singled out a landfill near Casablanca, Morocco, as a significant source of emissions visible from space. The findings raise questions over how well current reporting and modelling capture the extent of methane leaks from the waste sector.

Researchers led by GHGSat and other satellite-based teams surveyed 151 individual waste disposal sites across six continents using high resolution imagery. They found that satellite based estimates “generally show no correlation with reported or modelled emission estimates at facility scale.”

Methane from solid waste currently amounts to about 38 million tonnes per year which is roughly 10 per cent of total anthropogenic methane emissions and could rise to 60 million tonnes by 2050 if left unchecked.

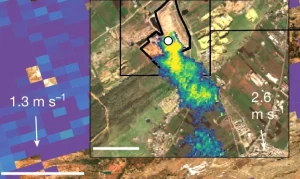

At the Casablanca site, satellite imagery captured emissions and surface activity changes showing how the open, non-covered parts of the facility were the dominant source of plumes. The researchers write in the Nature study that “the active surface is the dominant emission source across management and economic development levels.”

In the region around Casablanca the study reports that both plume origins detected by satellites and landfill surface activity show north-to-south migration as a new section of the landfill is developed.

According to local media like Hespress, satellites capable of detecting gas leaks as small as 25 by 25 metres flagged the Casablanca landfill as one of the spots where major methane leaks were occurring.

The article states that this detection underscores Morocco’s inclusion among “strongly emitting urban areas that include solid waste disposal sites as most prominent sources.”

The global implications are considerable as the study found that the top 40 per cent of sites (60 out of 151) accounted for 80 per cent of total detected emissions. In other words, a relatively small subset of “super-emitter” landfills dominates the waste sector’s methane footprint.

Moreover, though managed sanitary landfills showed lower emissions per area compared with informal dumping sites, when scaled up across all sites the mismatch between bottom-up models and the satellite findings remained large.

The researchers say that “independent observations of methane emitted from waste disposal sites are critical and can be obtained through … satellites” and emphasise that bridging the gap between bottom-up and top-down estimates is urgent.

If mitigation options such as banning organic waste in landfills, source separation, recycling and treatment via anaerobic digester are fully implemented, the study suggests methane emissions from solid waste might be reduced to as low as 11 million tonnes per year by 2050.

For Morocco and the larger North African region, the satellite detection of the Casablanca landfill leaks offers both a warning and a possible opportunity. Better capture of methane, covering of open sites, improved waste-management practices and real-time monitoring could both limit climate forcing and reduce lost energy resources.

In summary, the waste disposal sector and in particular landfills like the one near Casablanca may be leaking far more methane than modelled and satellites are now revealing these “hidden” sources. Action to improve waste management systems could deliver a significant climate benefit as well as reducing emissions.

Nature Journal, Hespress and Maghrebi.org

Want to chase the pulse of North Africa?

Subscribe to receive our FREE weekly PDF magazine