Mohamed Chebaro: EU migration reform faces uphill start

As if the EU as a bloc or Europe’s nation states needed the latest US National Security Strategy to add to the adversities and challenges that have been piling up against them in recent years. The strategy paper, published last week, claims that European nations stand on the brink of “civilizational erasure” and warns that, within a few decades, certain NATO member states’ populations might become majority non-European.

The far right in Europe has been using such a narrative — that the EU is facing a mass migration threat that is bigger than the Russian threat — for the past decade in a bid to gain power across the continent. It runs on a ticket of race, Christianity, nationalism and racial dominance, pitting people and countries against each other at a time when population aging across the continent makes the need for newcomers imperative. Otherwise, who will work the low-paid jobs in, for example, the care sector — to primarily look after that same aging population?

The US strategy corresponds with a sentiment in Europe that is gaining traction by blaming migrants for rising costs and dwindling integration within the EU, which itself is accused of failing to stem the flow of immigration due to the nature of the slow consensus-building process inbuilt in its institutions. So, the questions of asylum and migration become a conduit to gain attention and rise to power, regardless of the proof that their claims are overexaggerated and the fact that their tabled solutions are poor responses to the issue.

Meanwhile, the right-wing and populist media continues to frame newcomers to the EU as an existential threat to its people, sowing hate and fear among the so-called indigenous population of a potential change to their cultural, racial and religious composition.

Driven by the fear of far-right parties making gains at the ballot box, governments across Europe are scrambling to take a tougher stance on migration. On December 8, EU countries agreed to a draft proposal to set up “return hubs” for asylum seekers outside the bloc, mimicking the yet-to-be-tested Italian plan to process applicants in Albania and the now-scrapped British scheme for Rwanda.

This EU-wide returns plan could be an ambitious policy that fails to launch, as it will not be easy to strictly regulate centers that are outside the EU’s borders — safe countries to which migrants will be removed even if it is not their place of origin. The plan also includes imposing harsher penalties on failed applicants who refuse to leave. Approving such a policy is one thing, but tailoring it to comply with the myriad laws and ethics across various nations is another.

It seems that EU countries have cleared such hurdles theoretically, setting in motion these new asylum rules, adopting a common EU list of “safe countries of origin” and creating an EU-wide policy for migrant returns, despite strong criticism from more than 200 human rights and migrant organizations. The European Commission’s proposals will become law if the European Parliament endorses the final text.

EU countries also agreed on their “solidarity pool” for 2026, through which they can decide whether to help Mediterranean states with 21,000 relocations or by providing €420 million ($488 million) in financial contributions.

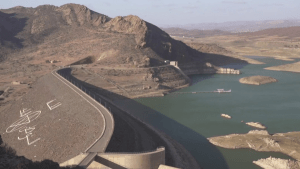

Under the proposed rules, an EU country will be able to reject an asylum application if the person could have received protection in a country the bloc considers safe. Broadly speaking, that means the member states agreeing that EU accession candidate countries should be designated as safe for asylum seekers, along with Bangladesh, Colombia, Egypt, India, Morocco and Tunisia, for example.

The European Council also agreed its position on creating EU-wide rules on returns, including obligations on those issued with return orders for the first time and penalizing those who fail to leave voluntarily, with possible prison time for noncooperation.

Critics of the plan fear that the new measures, if approved, would mirror the “dehumanizing” approach adopted by the US. They believe the hubs could be an ineffective and cruel scheme that simply aims, in a misguided way, to ramp up deportations, raids, surveillance, detention and, above all, discrimination.

The strategy paper claims that European nations stand on the brink of “civilizational erasure” and warns that, within a few decades, certain NATO member states’ populations might become majority non-European.

So, one wonders if US-style immigration and deportation enforcement is likely to come to Europe, knowing that trends established and used by US policymakers often filter through to Western Europe. Maybe this is a long shot for now but, as the extreme right continues its surge in the polls and US-driven ideological and practical interference is ongoing under the guise of protection of freedom of expression, what is inconceivable today could become policy tomorrow.

Overall, the EU has witnessed a decline in irregular entries to its territories, with figures showing a 20 percent drop so far in 2025 compared to last year. Such numbers, however, have failed to ease the pressure on politicians. Also, the new proposals come just a few months after the EU adopted a new set of migration laws that will come into effect next June.

The pitfalls of such policies are numerous, especially when nations try to adopt a common list of safe countries in a conflictive world, where countries designated as safe today may fall into many subjective categories tomorrow. They could even be open to endless challenges in human rights courts.

READ: Andrew Hammond: Macron seeks reset in China ties

But despite the legal limbo and effectiveness potholes, the EU plan is driven by the fears of center-right and far-right lawmakers, who are bent on showing their electorates they are acting. However, solidarity is nonexistent across the EU, with no countries wanting to take in extra asylum seekers. And here we are talking about sharing just 30,000 asylum seekers to relieve the pressure on countries that see large numbers of arrivals, like Greece and Italy.

Putting the high costs of this rather ineffective plan aside, taking in extra asylum seekers is fraught with political risks. Hence, the EU-wide common migration reforms remain an ambitious plan that will most likely fail to launch.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Maghrebi.org. Mohamed Chebaro is a British-Lebanese journalist with more than 25 years’ experience covering war, terrorism, defense, current affairs and diplomacy.

If you wish to pitch an opinion piece, please send your article to grace.sharp@maghrebi. org.

Want to chase the pulse of North Africa?

Subscribe to receive our FREE weekly PDF magazine