Hafed Al-Ghwell: How corruption fuels Libya’s unseen war

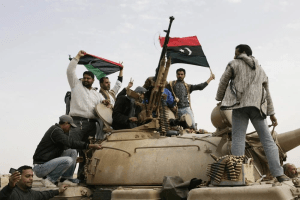

In Libya, the language of state-building is often just a dialect of theft. While political leaders publicly champion sovereignty and institutional reform, their private battles are waged over control of money flows, government contracts, and the influence these bring. This unseen war has hollowed out the state, creating a system where public institutions function as private treasuries for armed factions and their political sponsors.

The recent power struggles in western Libya are the logical outcome of an operating model where corruption is not a side effect but the central purpose of governance.

Under the Government of National Unity in western Libya, this model was perfected. The real governance occurred not in ministerial meetings but through shadowy networks where security figures placed loyalists across ministries and state-owned companies. For years, Abdulghani Al-Kikli, known as Ghneiwa, was a titan of this system. As head of the Security Support Apparatus, he installed allies in key offices to manipulate payrolls, secure kickbacks, and launder money. His power was built on turning public agencies into instruments of personal enrichment.

But in a system with finite spoils, every alliance has an expiration date.

Ghneiwa’s growing dominance alarmed his partners. In May 2025, a coalition led by the 444th Brigade lured Ghneiwa to his death and dismantled his militia. The operation was framed as a move to strengthen state control. In reality, it was a hostile takeover, a violent reshuffling of the deck that changed the players but not the game.

Into the power vacuum stepped Deputy Defense Minister Abdulsalam Al-Zoubi, a former ally of Ghneiwa. Al-Zoubi’s rise exemplifies the fluid loyalties of Libyan politics, where partnership is fleeting and power is permanent. He quickly absorbed much of Ghneiwa’s network, establishing himself as the new face of western Libyan security. His primary source of influence was control over the Administrative Control Authority and, crucially, the Contracts Review Office. This office is the nexus of the system; it approves every major government contract, allowing its controller to demand bribes for approval, block rivals, and push through lucrative deals for allies.

The recent power struggles in western Libya are the logical outcome of an operating model where corruption is not a side effect but the central purpose of governance.

Al-Zoubi and Ghneiwa had previously exploited this office with impunity. One brazen example involved the General Electricity Company of Libya. They approved a contract to import electricity meters at a grossly inflated price, pocketing the difference. In another scheme, they authorized the illegal export of scrap metal to Turkiye through a company owned by Al-Zoubi’s brother. This was not governance; it was a heist administered by a government office.

The linchpin of accountability, however, proved to be Audit Bureau chief Khalid Shakshak. He successfully challenged the law that handed the Contracts Review Office to Al-Zoubi’s authority, with Libya’s Supreme Court eventually ruling the move unconstitutional. This judicial decision was a direct blow to Al-Zoubi’s revenue stream, cutting him off from the lifeblood of his power.

The current stalemate is, therefore, highly volatile.

Al-Zoubi is unlikely to accept this loss passively. Any attempt by him to forcibly retake control of the Contracts Review Office from Shakshak could easily trigger another round of street fighting in Tripoli. Furthermore, in this environment, today’s allies are tomorrow’s rivals. Just as Al-Zoubi betrayed Ghneiwa, his own partners may soon see him as the next obstacle to their ambitions.

This self-cannibalizing cycle in the west is mirrored by a more consolidated kleptocracy in the east. Khalifa Haftar and his sons have transformed their territorial control into an economic empire with no oversight. Their dominance is built on similar pillars: commandeering public budgets and orchestrating illicit revenue streams. A primary example is the massive fuel-smuggling scheme orchestrated by Saddam Haftar.

By exploiting Libya’s bloated fuel subsidy program, his network siphons off billions of dollars annually, selling subsidized diesel on the black market and depriving the state of crucial hard currency. This starves the national economy and fuels inflation, hurting ordinary Libyans. To date, the Haftars have industrialized corruption, using their armed dominance to coordinate smuggling routes by land and sea, with the proceeds strengthening their grip on power and even fueling conflicts in neighboring countries such as Sudan.

The international community often misreads this chaos.

Figures like Al-Zoubi are frequently treated as stabilizers and reliable partners. World powers, including the US, France, and Turkey, engage with them as bridges between east and west or as bulwarks against terrorism. This engagement is a fatal miscalculation. It mistakes a temporary strongman for a foundation of stability. By granting these figures legitimacy and diplomatic cover, the international community removes any incentive for reform.

This unseen war has hollowed out the state, creating a system where public institutions function as private treasuries for armed factions and their political sponsors.

It rewards the very behavior that perpetuates the crisis. The recent illegal detention of Mohammed Mensli, head of Libya’s Asset Recovery and Management Office, is a case in point. Just as Mensli was on the verge of recovering billions in stolen state assets, he was arrested and held without trial. His imprisonment is widely seen as an effort by corrupt networks to seize control of those assets or silence a threat. The muted response from many international capitals in the face of such acts speaks volumes.

Libya is thus trapped in a feedback loop of predation.

The western system constantly collapses in on itself as rivals battle for a larger share of a shrinking pie. The eastern system feigns as a disciplined criminal enterprise, extracting wealth with brutal efficiency. Both models are sustained by foreign powers that prioritize short-term security cooperation or commercial contracts over genuine stability.

The pattern is not new, but its consequences are becoming harder to ignore. Libya keeps recycling the same elites, each claiming to secure the state while fighting over the same revenue streams. The system collapses not from lack of capacity but from the way capacity is intentionally repurposed. Every office becomes a prize. Every alliance has an expiry date. Every attempt at reform becomes a redistribution of rents dressed as governance.

READ: Dr Ngozi Erondu: US health strategy risks widening inequality

Until this calculus changes, Libya will remain a country consumed by its leaders, a nation where the fight to build a state is lost to the endless, unseen war over who gets to loot it. Libya’s instability is, therefore, not driven by ideology, foreign actors, or structural weakness alone. It is driven by a competition for money, contracts, and influence that has replaced the state itself — leaving the country to continue feeding on its own institutions, as the ruling elites mistake the pursuit of personal gain for political strategy.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Maghrebi.org. Hafed Al-Ghwell is a senior fellow and executive director of the North Africa Initiative at the Foreign Policy Institute of the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, DC. X: @HafedAlGhwell.

If you wish to pitch an opinion piece, please send your article to grace.sharp@maghrebi.org.

Want to chase the pulse of North Africa?

Subscribe to receive our FREE weekly PDF magazine